Ryan Bourne on the British growth deterioration

From the London Times (gated), he starts from my earlier MR discussion of the topic:

Yet, from a policy perspective, identifying what changed after 2008 is less interesting than what could have been done better. Cowen’s question was ignited by a British entrepreneur telling him that the UK’s planning laws explain much of the enduring prosperity gap to the United States. I agree, and think that Cowen understates the damage of nimbyism after 2008. The financial crisis headwinds made it more imperative to dismantle growth-stifling land-use barriers, which are becoming increasingly damaging with time.

Careful analysis by the LSE economists John Van Reenen and Xuyi Yang suggests the UK has a sharper deterioration in productivity growth than France or Germany because of weaker capital investment, which the financial crisis, Brexit and political uncertainty have exacerbated. We can’t undo the financial crisis or easily overturn the public’s decision on Brexit, but giving the green light to more housing, energy and infrastructure projects by liberalising land use was an obvious path to countering this investment collapse…

Prior to 2008, pharmaceuticals, chemicals, and life sciences were expanding strongly, but are increasingly hampered by land rationing and escalating rental costs, too. Savills estimated in 2020, for example, that London had 90,000 sq ft and Manchester 360,000 sq ft of suitable lab space available, compared with Boston’s 14.6 million sq ft and New York’s 1.36 million sq ft. Similar problems afflict efforts to build hyperscale data centres.

This is all worth a ponder. Claude 3 estimates that land rent is 12-15% of British gdp, so I still would like to see a very careful decomposition done here. I estimated the NIMBY issues accounted for about 15% of the gdp shortfall, if we relaxed NIMBY quite a bit how much upside would that create?

My Conversation with the excellent Coleman Hughes

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is part of the episode summary:

Coleman and Tyler explore the implications of colorblindness, including whether jazz would’ve been created in a color-blind society, how easy it is to disentangle race and culture, whether we should also try to be ‘autism-blind’, and Coleman’s personal experience with lookism and ageism. They also discuss what Coleman’s learned from J.J. Johnson, the hardest thing about performing the trombone, playing sets in the Charles Mingus Big Band as a teenager, whether Billy Joel is any good, what reservations he has about his conservative fans, why the Beastie Boys are overrated, what he’s learned from Noam Dworman, why Interstellar is Chris Nolan’s masterpiece, the Coleman Hughes production function, why political debate is so toxic, what he’ll do next, and more.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: How was it you ended up playing trombone in Charles Mingus Big Band?

HUGHES: I participated in the Charles Mingus high school jazz festival, which they still do every year. It was new at the time. They invite bands from all around to audition, and they identify a handful of good soloists and let them sit in for one night with the band. I sat in with the band, and the band leader knew that I lived close by in New Jersey, and so essentially invited me to start playing with the band on Monday nights.

I was probably 16 or 17 at this point, so I would take the NJ Transit into New York City on a Monday night, play two sets with the Mingus Band sitting next to people that had been my idols and were now my mentors — people like Ku-umba Frank Lacy, who is a fantastic trombone player; played with Art Blakey and D’Angelo and so forth. Then I would go home at midnight and go to school on Tuesday morning.

COWEN: Why is the music of Charles Mingus special in jazz? Because it is to me, but how would you articulate what it is for you?

Here is another:

COWEN: If I understand you correctly, you’re also suggesting in our private lives we should be color-blind.

HUGHES: Yes. Broadly, yes. Or we should try to be.

COWEN: We should try to be. This is where I might not agree with you. So I find if I look at media, I look at social media, I see a dispute — I think 100 percent of the time I agree with Coleman, pretty much, on these race-related matters. In private lives, I’m less sure.

Let me ask you a question.

HUGHES: Sure.

COWEN: Could jazz music have been created in a color-blind America?

HUGHES: Could it have been created in a color-blind America — in what sense do you mean that question?

COWEN: It seems there’s a lot of cultural creativity. One issue is it may have required some hardship, but that’s not my point. It requires some sense of a cultural identity to motivate it — that the people making it want to express something about their lives, their history, their communities. And to them it’s not color-blind.

HUGHES: Interesting. My counterargument to that would be, insofar as I understand the early history of jazz, it was heavily more racially integrated than American society was at that time. In the sense that the culture of jazz music as it existed in, say, New Orleans and New York City was many, many decades ahead of the curve in terms of its attitudes towards how people should live racially: interracial friendship, interracial relationship, etc. Yes, I’d argue the ethos of jazz was more color-blind, in my sense, than the American average at the time.

COWEN: But maybe there’s some portfolio effect here. So yes, Benny Goodman hires Teddy Wilson to play for him. Teddy Wilson was black, as I’m sure you know. And that works marvelously well. It’s just good for the world that Benny Goodman does this.

Can it still not be the case that Teddy Wilson is pulling from something deep in his being, in his soul — about his racial experience, his upbringing, the people he’s known — and that that’s where a lot of the expression in the music comes from? That is most decidedly not color-blind, even though we would all endorse the fact that Benny Goodman was willing to hire Teddy Wilson.

HUGHES: Yes. Maybe — I’d argue it may not be culture-blind, though it probably is color-blind, in the sense that black Americans don’t just represent a race. That’s what a black American would have in common — that’s what I would have in common with someone from Ethiopia, is that we’re broadly of the same “race.” We are not at all of the same culture.

To the extent that there is something called “African American culture,” which I believe that there is, which has had many wonderful products, including jazz and hip-hop — yes, then I’m perfectly willing to concede that that’s a cultural product in the same way that, say, country music is like a product of broadly Southern culture.

COWEN: But then here’s my worry a bit. You’re going to have people privately putting out cultural visions in the public sphere through music, television, novels — a thousand ways — and those will inevitably be somewhat political once they’re cultural visions. So these other visions will be out there, and a lot of them you’re going to disagree with. It might be fine to say, “It would be better if we were all much more color-blind.” But given these other non-color-blind visions are out there, do you not have to, in some sense, counter them by not being so color-blind yourself and say, “Well, here’s a better way to think about the black or African American or Ethiopian or whatever identity”?

Interesting throughout.

What should I ask Philip Ball?

Yes I will be doing a Conversation with him. Here is Wikipedia:

Philip Ball (born 1962) is a British science writer. For over twenty years he has been an editor of the journal Nature, for which he continues to write regularly. He is a regular contributor to Prospect magazine and a columnist for Chemistry World, Nature Materials, and BBC Future.

Ball holds a degree in chemistry from Oxford and a doctorate in physics from Bristol University.

He has written more science books than I can count (see Wikipedia), on a wide variety of topics, and I very much liked his latest book How Life Works: A User’s Guide to the New Biology. How many people have demonstrated a greater total knowledge of science than he has?

So what should I ask him?

Are Hungarian pro-fertility policies failing?

Hungary-like fertility policies flatly don't work.

Hungary has dedicated major resources to this – no taxes for 3+ kids, debt forgiveness, major subsidies for homes. It's actually equivalent to ~5% of their GDP. The US military is 3.2%, so big spending.

Nothing happened. https://t.co/ICmu43cieu pic.twitter.com/VNWRctggwc

— Hunter📈🌈 (@StatisticUrban) April 29, 2024

Or is it too soon to tell? Are we underestimating supply elasticities? Or are they truly low?

Wednesday assorted links

1. Roots of Progress blog building fellowship.

2. MIE: buy a decommissioned USG supercomputer.

3. Paul Auster, RIP, here is a recent tweet of mine on Auster and writing.

4. A reconstruction of ancient Greek music.

5. Talent reform for Whitehall?

6. What were the Roman dodecahedrons used for?

7. New paper on housing supply elasticities, for instance: “Building renovations that add units and reduced teardown rates together account for about 40% of unit supply responses to price growth.”

Trump and the Fed

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one bit:

Trump advisers have been drafting plans to limit significantly the operating autonomy of the Fed. The Trump campaign has disavowed these plans, but the general ideas have been spreading in Republican circles, as evidenced by the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 report. Trump himself has called for a weaker dollar policy, which could not be carried out without some degree of Fed cooperation. As a former businessman and real-estate developer, Trump seems to care most about interest rates, banking and currencies.

One concrete proposal reported in the Wall Street Journal would require the Fed to informally consult with the president on decisions concerning interest rates and other major aspects of monetary policy. That would make it harder for the central bank to commit to a stated policy of disinflation, since the ongoing influence of the president would be a wild card in the decision. Presidents would likely give more consideration to their own reelection prospects than to the advice of the Fed staff. Further confusion would result from the reality that the responsibility of the president in these matters simply would not be clear.

It’s important not to be naïve: Regardless of who is in the White House, the Fed already cares what the president and Congress think, as its future independence is never guaranteed. Still, explicit consultation would undercut the coherence of the decision-making process within the Fed itself and send a negative signal to investors. There is no upside from this approach.

There is much more at the link.

What I’ve been reading

Benjamin Nathans, To The Success of Our Hopeless Cause: The Many Lives of the Soviet Dissident Movement. The definitive book on its topic, consisting largely of profiles of dissidents. The title is taken from a longstanding dissident toast, and yet they won eventually, sort of. So your cause isn’t hopeless either.

Scott Hodge, Taxocracy: What You Don’t Know About Taxes & How They Rule Your Daily Life. An excellent short book on the power of tax incentives, written by the former head of the National Tax Foundation. Incentives matter!

Alex Christofi has written Cypria: A Journey to the Heart of the Mediterranean, which is the book I will take to Cyprus when I go there.

Randy Barnett, A Life for Liberty: The Making of an American Originalist, is a 616 pp. well-written memoir of a prominent libertarian legal theorist.

Gregory Makoff, Default: The Landmark Court Battle over Argentina’s $100 Billion Debt Restructuring. This is both a good book on how the law handles sovereign defaults and useful background to what Milei is trying to undo in Argentina.

I’ve also been reading a cluster of books on the history of the transgender movement. I don’t have a single go-to book to recommend, but you could start with Weininger and Magnus Hirschfeld, who are also interesting representatives of Austro-Hungarian and Germanic culture in the early twentieth century. Overall, I am surprised how many of the key books are out of print, selling used for high prices on Amazon.

Will Japan have a financial crisis anytime soon?

The odds are against this, and most market prices are well-behaved, noting that the yen was hitting 160 to the dollar. More importantly, Japanese stocks have bounced back over the last two years, over the same time period that the yen has been weakening. That is one marker that this is a needed adjustment, rather than a pending collapse. Noah has a good post on the whole topic. Here are a few related observations:

1. When it comes to a mature, functional economy, do not bet on a financial crisis. Such crises are the exceptions. Furthermore, financial crises, by their very nature, are nearly impossible to predict in economies with functioning financial markets. If the prediction were a good one, the crisis already would be here.

2. That said, crises do occur, and economies can have hidden sources of leverage. The 1990s Asian financial crisis was not obvious in advance, and throughout South Korea had a strong long-run fiscal position, due to growing export potential. So talking about this is not a waste of time.

3. The real question is what Japan will do with all of its government debt, combined with a shrinking population. Note that the debt to gdp ratio is sometimes estimated at 260%, though much of this (half?) is held by the Bank of Japan. That said, I am not sure the relevance of the BOJ-held debt should be dismissed entirely. It still means the Bank is less solvent, and whether debt monetization/money printing is an automatic way to overcome that dilemma I consider in #4. Institutional barriers still do matter somewhat.

4. Japanese short-term interest rates are again very close to zero. So it is hard to inflate the debt away by an asset swap, as the “new money” might simply be saved and prove irrelevant. It is true that the Japanese central bank could try to credibly promise to keep inflating the actual paper currency until price inflation went up. But that kind of inflation is hard to predict and control, so perhaps such a promise would be a) not credible, and b) unwise. “We’re going to goose up the printing presses (literally, not metaphorically) until price inflation breaks double digits!” does not do wonders for a country’s credibility, fiscal or otherwise.

4b. It is hard to raise real interest rates, because the long-term fiscal position of the government is so difficult.

5. Japan as a whole has a very strong external position and foreign asset portfolio. Nonetheless the extent to which any of that can help Japan address its long-term solvency problem is an open question. Is the Japanese treasury going to start confiscating the Toyota plant in Kentucky?

In this regard I am somewhat less sanguine than are many of the optimists. A falling yen redistributes wealth from the Japanese consumers who buy imported food (directly), and energy (indirectly), and to Japanese MNEs holding dollars. But how much do one-time boosts in “corporate stock solvency” protect against longer-run growth unsustainabilities? I would not bet the house on that one.

6. Similarly, I am not so impressed by the strong dollar holdings of the Bank of Japan. In times of currency crisis, such reserves can be burned through quickly, as evidenced by South Korea right before the 1990s Asian financial crisis. Let’s say your total government debt is about $9 trillion, and the BOJ holds a trillion in USD. That is a nice cushion, but it is not going to save the day, especially since Japanese government debt will accumulate further with unfavorable demographics.

7. If you think about the political economy of the status quo, it is a bit worse than is being recognized. Inducing “austerity” through the exchange rate movement means that the redistribution from citizens goes to Japanese corporations, rather than to the government coffers, to pay off or retire debt. That makes tax hikes all the harder later on. You might rather have had the direct government austerity now in lieu of the exchange rate adjustment. How good a political message is the following?: “We know you’ve been hammered by higher prices for imported energy and food, but don’t worry, we’re going to take care of everything with a big tax hike.”

8. When push comes to shove, do markets believe that the Japanese government could see through a big tax hike? With the tax take currently at about 34% of gdp, well below western European levels, I’m still going to say yes. And if markets believe such a tax hike is possible, perhaps it is not anytime soon required. That is a core reason why I would bet against a financial crisis here.

9. Perhaps the true wild card is China, and the risk of contagion, no matter in which direction the contagion might run. Who really knows what is going on in the Chinese economy right now? I certainly don’t. It would however be a nightmare scenario if the world’s #2 and #3 economies, at the same time, had major financial troubles, including those of capital outflow.

Tuesday assorted links

1. Greenpeace vs. Golden Rice. And Michael Magoon essays on Progress Studies.

3. Good piece on Derek Parfit.

4. The case for permitting reform is stronger than you think.

5. GPT2 speculation.

6. UK metascience research grant call.

7. Scott Alexander now has a proper response to Robin on health care. And Robin’s response.

False Necessity is the Mother of Dumb Invention

Recently, I have seen two innovations in retail, AI cashiers and human cashiers but working remotely from another country such as the Philippines and making much lower wages than domestic workers (examples are below). I fear that the AI cashiers will outcompete the Philippine cashiers leading to the worst of all worlds, AIs doing low-productivity work. In an excellent piece, People Over Robots, Lant Pritchett nails the problem:

Barriers to migration encourage a terrible misdirection of resources. In the world’s most productive economies, the capital and energies of business leaders (not to mention the time and talents of highly educated scientists and engineers) get sucked into developing technology that will minimize the use of one of the most abundant resources on the planet: labor. Raw labor power is the most important (and often the only) asset low-income people around the world have. The drive to make machines that perform roles that could easily be fulfilled by people not only wastes money but helps keep the poorest poor.

The knock on immigration has always been “we wanted workers, we got people instead.” But, with remote workers, we can get workers without people! Even Steve Sailer might approve.

At the same time, the use of AI for cashiers illustrates Acemoglu’s complaint about “so-so automation,” automation that displaces labor but with low productivity impact. AI cashiers are fine but how big can the gains be when you are replacing $3 an hour human labor?

It seems likely that at least one of these innovations will become common. Unfortunately, I suspect that US workers will object more to $3 an hour remote workers taking “their jobs” than to AI. As a result, we will get AI cashiers and labor displacement of both US and foreign workers. Doesn’t seem ideal. It’s not obvious how to direct technology to higher productivity tasks and tasks complementary to human labor but at the very least we shouldn’t artificially raise the price of labor to make AI profitable.

As Pritchett notes this is hardly the first time that cuffing labor leads to the creation of unnecessary technology.

In the middle of the twentieth century, the United States allowed the seasonal migration of agricultural guest workers from Mexico under the rubric of the Bracero Program. The government eventually slowed the program and finally stopped it entirely in 1964. Researchers compared the patterns of employment and production between those states that lost Bracero workers and those that never had them. They found that eliminating these workers did not increase the employment of native workers in the agricultural sector at all. Instead, farmers responded to the newly created scarcity of workers by relying more on machines and technological advances; for instance, they shifted to planting genetically modified products that could be harvested by machines, such as tomatoes with thicker skins, and away from crops such as asparagus and strawberries, for which options for mechanized harvesting were limited.

Necessity may be the mother of invention, but false necessity is the mother of dumb inventions.

Wendy’s AI.

Updated estimates on immigration and wages

In this article we revive, extend and improve the approach used in a series of influential papers written in the 2000s to estimate how changes in the supply of immigrant workers affected natives’ wages in the US. We begin by extending the analysis to include the more recent years 2000-2022. Additionally, we introduce three important improvements. First, we introduce an IV that uses a new skill-based shift-share for immigrants and the demographic evolution for natives, which we show passes validity tests and has reasonably strong power. Second, we provide estimates of the impact of immigration on the employment-population ratio of natives to test for crowding out at the national level. Third, we analyze occupational upgrading of natives in response to immigrants. Using these estimates, we calculate that immigration, thanks to native-immigrant complementarity and college skill content of immigrants, had a positive and significant effect between +1.7 to +2.6\% on wages of less educated native workers, over the period 2000-2019 and no significant wage effect on college educated natives. We also calculate a positive employment rate effect for most native workers. Even simulations for the most recent 2019-2022 period suggest small positive effects on wages of non-college natives and no significant crowding out effects on employment.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Alessandro Caiumi and Giovanni Peri. I wouldn’t say I have massive trust in this kind of estimate. What I do notice, however, is the utter lack of countervailing real wage estimates that show immigration to be a major negative for U.S. native workers.

Dean Ball on the new California AI bill (from my email)

SB 1047 was written, near as I can tell, to satisfy the concerns of a small group of people who believe widespread diffusion of AI constitutes an existential risk to humanity. It contains references to hypothetical models that autonomously engage in illegal activity causing tens of millions in damage and model weights that “escape” from data centers—the stuff of science fiction, codified in law.

The bill’s basic mechanism is to require developers to guarantee, with extensive documentation and under penalty of perjury, that their models do not have a “hazardous capability,” either autonomously or at the behest of humans. The problem is that it is very hard to guarantee that a general-purpose tool won’t be used for nefarious purposes, especially because it’s hard to define what “used” means in this context. If I use GPT-4 to write a phishing email against an urban wastewater treatment plan, does that count? Under this bill, quite possibly so.

If, back in the 70s, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak had to guarantee that their computers would not be used for serious crimes, would they have been willing to sign with potential jail time on the line? Would they have even bothered to found Apple?

Finally, because of its requirements (or very strong incentives) for developers to monitor and have the means to shut off a user’s access, the bill could make it nearly impossible to open-source models at the current AI frontier—much less the frontiers of tomorrow.

And here is Dean’s Substack on emerging technology (including AI) and the future of governance.

On deficient British growth (from the comments)

Monday assorted links

1. Self-navigating car navigating traffic in India.

2. Do progressive prosecutors lead to higher crime rates?

4. California bill to regulate AI models.

5. “Yann LeCun says in 10 years we won’t have smartphones, we will have augmented reality glasses and bracelets to interact with our intelligent assistants” Link here.

6. Hollywood movies embrace sex once again (NYT).

7. The Manning, Zhu, and Horton paper is now an NBER working paper.

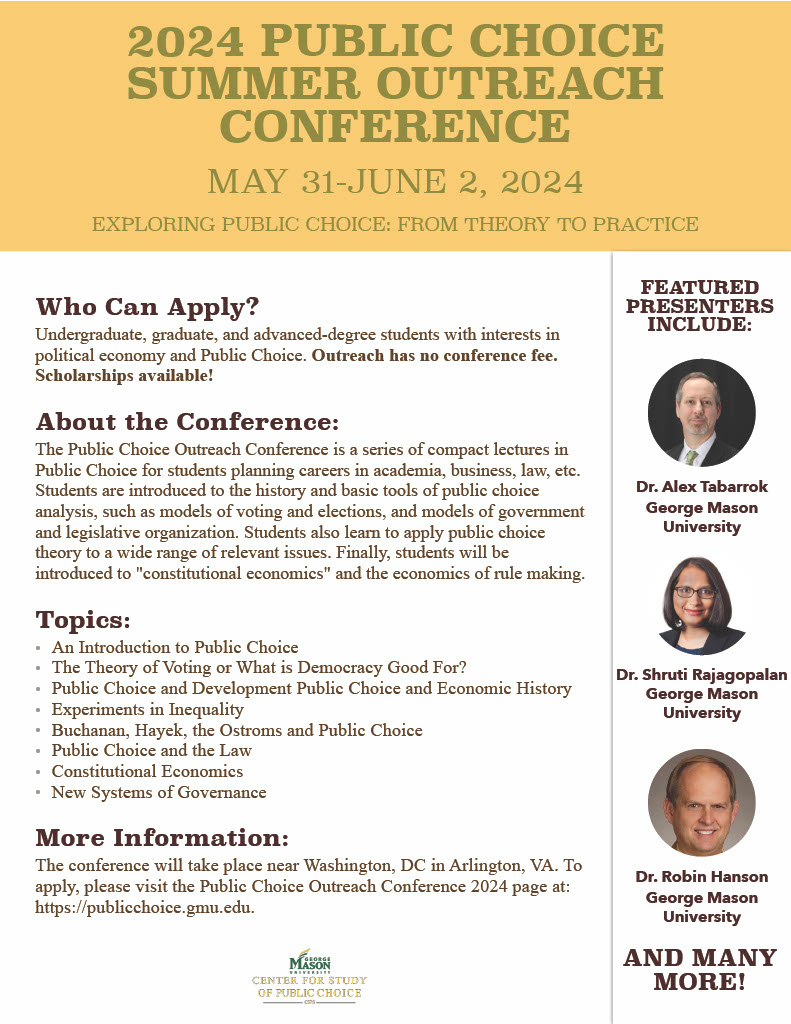

Public Choice Outreach!

There are just a few spots left for the Public Choice Outreach Conference! This is a great opportunity to hear from excellent speakers including Garett Jones, Peter Boettke, Johanna Mollerstrom and more! The conference is a crash course in public choice. It’s entirely free. Indeed scholarships are available! More details in the poster. Please pass around. Applications are here!

That is from Phil S. As a macroeconomist, Fischer Black remains underrated.